Precocious isn’t normally a word associated with a septuagenarian. But if life’s twilight years are a second childhood, perhaps the sprightly reveries of an aging novelist recovering from a bump on the head might veer into a kind of childish precocity. George Irving Newett, the 77-year-old novelist narrating John Barth’s Every Third Thought: A Novel in Five Seasons (Counterpoint, 2011), suffers the aforementioned trauma on his 77th birthday, one year after a tropical storm destroyed the community where George and his wife, Amanda Todd, lived on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. That storm hit on the 77th anniversary of the 1929 stock market crash, and Newett, a self-professed “old fart fictionist” of the postmodern variety, views the numerical parallel of the events as no mere coincidence.

That’s not all that Newett sees, nor the last of Barth’s parallels and layers. Barth, A&S ’51, ’52 (MA), a retired Writing Seminars faculty member, has long been literature’s imp, mastering storytelling styles and structures only to pull at their seams to expose the author lurking in the background. And in Every Third Thought Barth infuses the novel with Shakespeare—the title is cribbed from The Tempest—much as he steeped his 1973 National Book Award winner, Chimera, in folktales and myths.

After his tumble, Newett has a series of seasonal visions—fall, winter, spring, summer—that inspire him to leaf through his life and memories, each a set of stories that often search for a reliable narrator. One dependable source may be Newett’s childhood best friend Ned Prosper, who also became a writer, and who may have started a novel called Every Third Thought. Perhaps there’s something in that manuscript that could inspire Newett to craft his own “great American goddamned novel.” Perhaps he could even appropriate that text a bit. As Newett notes, “By the October of one’s life as a reader, writer, and professor of literature, what hasn’t been said already?”

For all of its belletristic gambits—the Shakespearean allusions, the near constant wordplay, the almost annoying alliteration addiction—what stands out brightest in Every Third Thought is an intimate and enviable portrait of life partners. Barth’s Newett and Todd aren’t merely husband and wife—they’re each other’s best editor, the ideal audience for jokes, the perfect travel companion, the with-whom-the-pizza-is-shared, the without-whom-none-of-this-matters. And over its forked path, Every Third Thought eventually becomes a streamlined, devastating story of moving from those robust years when you take stock of first times to wondering if this moment could be a last, and it does so with a tireless conviction that language has the capacity to animate every step of life’s cruel slouch toward its end.

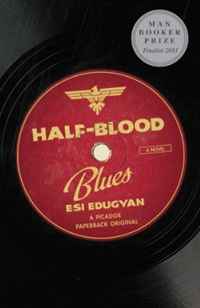

NAZI-OCCUPIED PARIS is no place for Hieronymus Falk, the center of Canadian writer Esi Edugyan’s second novel, Half-Blood Blues. The French distrust him because he’s German, and the Nazis won’t accept him because he’s the biracial son of an African man and a German woman. The preternaturally gifted jazz trumpeter had fled decadent 1930s Berlin for Paris with two African-American friends once it became clear the Nazis weren’t exactly into black jazzmen and the affluent Jews they palled around with. Now, as Paris empties and the Germans draw near, Falk’s biggest threat may be somebody he considers his best friend. Edugyan, A&S ’01 (MA), explores the lifelong scars of being black in Nazi-occupied Europe through Sidney Griffiths, the bass-playing Baltimorean who narrates Blues’ harsh tale. In 1992, widower Sid is convinced by his old friend and bandmate Chip to take part in, and eventually return to Berlin to see, a Falk documentary, which catalyzes Blues’ leaps through time to reveal the wartime stress and petty jealousies that shaped their lives. Picador releases Half-Blood Blues in the United States in early 2012. The novel has been shortlisted for no less than the Man Booker Prize and recently won the Scotiabank Giller Prize, awarded annually for the best Canadian novel or short-story collection written in English.