TSAVO, COLONIAL EAST AFRICA, 1898. It was another long night for Lieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson, a British civil engineer. Clutching his rifle, he crouched inside a deserted railway-camp hospital, waiting for the lions to return. A pair of them had been prowling around the camp together, killing the workers who were building a railroad through the region. The night before, one lion had burst through the old hospital tent, injuring two patients and dragging another to his death. Patterson ordered his workers to build a new infirmary, which they surrounded with a thick thorn-bush fence called a boma. He then camped at the old place, hoping to bag a lion. Shrieks from the new hospital broke his vigil.

He later wrote, “Our dreaded foes had once more eluded me.” During the night, one lion “managed to get its head in below the canvas, seized [a worker] by the foot and pulled him out. In desperation the unfortunate water-carrier clutched hold of a heavy box in a vain attempt to prevent himself being carried off, and dragged it with him until he was forced to let go. . . . [The lion] sprang at his throat and after a few vicious shakes the poor bhisti’s agonized cries were silenced forever. The brute then took him in his mouth, and, like a huge cat with a mouse, ran up and down the boma, looking for a weak spot to break through.”

Patterson eventually slew both lions, but not before they had killed as many as 135 people over a nine-month period, according to his account. The railway company would acknowledge only 28 deaths.

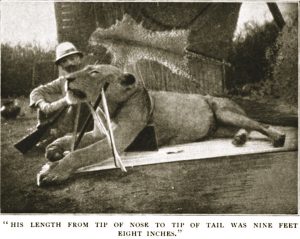

Patterson and his first kill, a lion measuring 9 feet, 8 inches from the tip of his nose to the tip of his tail. Photo courtesy of Field Museum, Chicago, IL

Flash forward a century to a movie theater near Johns Hopkins University’s Homewood campus. Nathaniel J. Dominy, A&S ’98, then a junior anthropology and English major, was on a date, watching a couple of huge cats spring across the screen. Val Kilmer played Colonel Patterson and Michael Douglas played a fictitious big-game hunter who took on the notorious Tsavo lions in The Ghost and the Darkness, directed by Stephen Hopkins. For his role, Kilmer won a Razzie Award for worst supporting actor, and the film was every bit as factual as it was well acted, though it did win an Oscar for sound effects editing. “It was perhaps not the best choice for a date movie,” Dominy admits.

But the story never left his memory. Now an associate professor of anthropology at University of California, Santa Cruz, Dominy studies the ecology and evolution of the human diet. In 2007, he received a prestigious David & Lucile Packard Foundation grant totaling $825,000 over five years (and in 2009 was named one of Popular Science magazine’s “Brilliant 10” scientists under 40) for his research. Last year, he veered a bit from his usual course of inquiry to collaborate with a UCSC doctoral candidate, Justin D. Yeakel, on a study of the Tsavo lions. The lions’ taxidermied remains still exist, and Dominy and Yeakel used a technique called stable isotope analysis to determine what they’d actually eaten more than a century ago. In the process, they rewrote a bit of history.

THE OFFICIAL NAME OF the African construction project was the Uganda Railway—hundreds of miles of track that would link the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa, in what is modern-day Kenya, to Kampala, Uganda. Detractors had a more colorful name for it—the “Lunatic Express.”

In the late 19th century, Europe was rushing to carve up the African continent. Germany had just annexed Tanganyika as German East Africa, and Britain wanted to prevent a similar takeover of Uganda. Building a railroad was one way to secure a stake in East Africa and its plentiful riches—ivory, tea, and salt, along with convertible souls for Christian missionaries. A railway would also make it possible to move goods into and out of the region without using slave labor, which Britain had outlawed earlier in the century. Queen Victoria, who supported Christian missionary work, was on board with the project. Abolitionists supported it, too. Many members of Parliament, however, balked at the price tag of 3 million pounds sterling. By its completion, the railway would prove even more costly—in pounds and in human lives.

Illustration by Stephanie Dalton Cowan